UK businesses may be neglected huge swathes of leadership talent, by overlooking unconscious biases relating to social class. A new report has found that – more than gender, ethnicity or sexuality – socio-economic background has the strongest effect on an individual’s career progression.

A study from the Bridge Group on behalf of KPMG has found that class remains the biggest barrier to employees as they seek to build their careers. The study saw the biggest ‘progression gap’ analysis ever published by a business, with experts from the Bridge Group analysing career paths of over 16,500 partners and employees at KPMG over a five-year period.

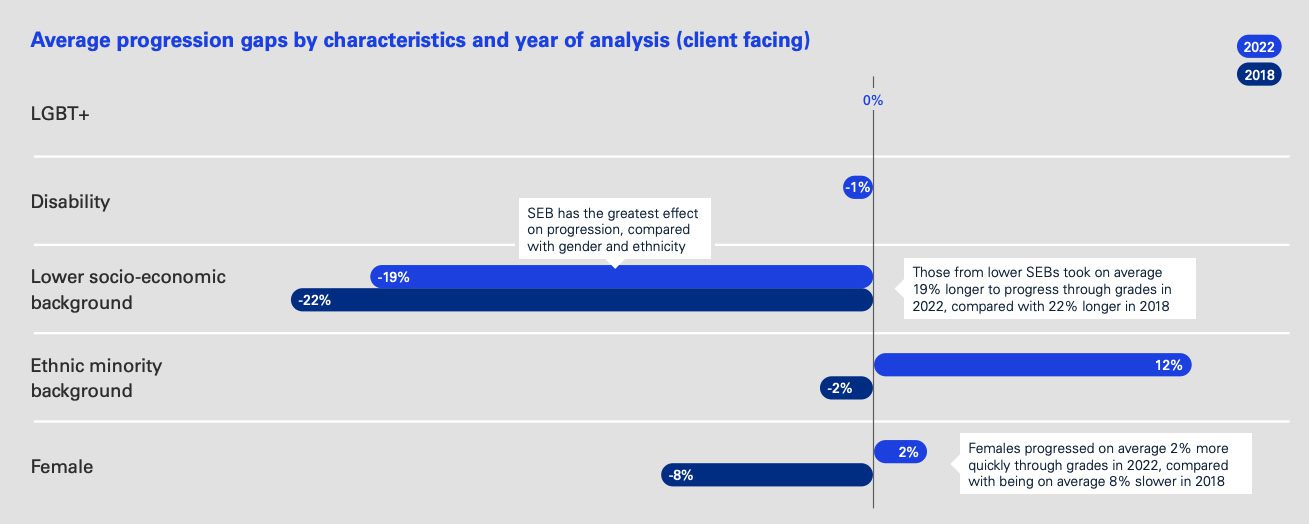

The team examined the average time it took individuals to be promoted, looking at their gender, ethnicity, disability, sexual orientation as well as socio-economic background. This revealed that employees from lower socio-economic backgrounds took around 19% longer to progress through grades within KPMG than those from higher socio-economic backgrounds. Meanwhile, as the firm’s targets on addressing gender and ethnicity gaps take effect, women and ethnic minority background progression is actually faster than other employees.

Jon Holt, Chief Executive of KPMG in the UK, commented, “Socio-economic background is complex and emotive. It requires us to confront how our upbringing shapes the opportunities we have access to later in life. But as businesses we need to lean into this discomfort if we are to make progress. Career advancement should be about realising potential, and not someone’s background or ‘polish’.”

The researchers noted that “fundamentally, KPMG’s workforce remains unrepresentative as a whole,” due to its positive progression rates for historically underrepresented groups – and these may well rise as the firm’s workforce becomes more diverse, before subsiding as workforce diversity becomes more equal. And looking ahead within the firm, KPMG may now also be able to do the same when it comes to social mobility.

Holt added, “This study is pioneering in its scope, and I hope adds value and rigour to the debate around social mobility. As a firm these insights are enabling us to take targeted action and we are publishing our findings so other organisations can draw insights from them and use it as a blueprint to measure and address barriers in their own businesses.”

Class ceiling

The impacts of the nascent steps the firm is taking to address its socio-economic gap may also explain why lower socio-economic backgrounds are mildly faster to move from Director to Partner – 2.3 years – than the 2.5 years it takes their higher socio-economic counterparts. However, it was markedly longer for people from lower income backgrounds to win promotion across all other ranks of the firm.

If this is the case within a firm which is looking to close its gap, it would suggest that socio-economic background is a far bigger factor in promotion across firms which are overlooking it. In the wider economy, for example, the number of employers offering apprenticeships – often seen as a keystone of social mobility, by enabling individuals from lower income backgrounds to learn on the job – fell from 85% in 2020 to 79% in 2022. This, along with a number of other factors, means those who start life with the least financial support, will struggle longer to obtain better-paid work.

Nik Miller, Chief Executive at the Bridge Group, added, “There remains a proven link between someone’s social background and their educational and employment outcomes and social inequality is estimated to cost the UK £39 billion per year. It is exacerbating lower levels of productivity, poor mental health, and diminishing people’s life expectancy… Progression is one of the truest indicators of inclusion in an organisation, across all and any diversity characteristics. KPMG’s research is pioneering, and we commend the firm for its leading-edge approach. The more we can highlight and understand the impacts of socio-economic background, including how it affects progression, the more we can create more equal outcomes for all.”