People in Britain are increasingly concerned by the gap between rich and poor – while few believe the government is ‘in touch’ with those realities. A new study suggests a majority of UK residents now support emergency help for making ends meet amid the cost-of-living-crisis.

In 2021, it was revealed by thinktank IPPR that 17.4% of working households were living in ‘relative poverty’ – up from 13% in 1996. The report blamed a combination of low wage rises and the spirallingcost of living faced by a group previously described by ex-Prime Minister Theresa May as the “just about managing”. Since then, the situation has only gotten worse – pushing an increasing portion of Britain’s population to rely on foodbanks, and to choose between heating their homes or purchasing other essentials.

At the same time, the UK’s super wealthy have arguably never had it so good. Many were able to capitalise on the Covid-19 crisis in spectacular fashion, to rapidly increase their respective hordes at record rates. During the pandemic with the richest 10% gaining £50,000 on average, dwarfing increases for the poorest third of the population, according to Resolution Foundation report. It may not surprise many people to discover that he UK’s top ten richest people are wealthier than the group has ever been, then. According to The Sunday Times’ annual Rich List, the cumulative wealth of the UK’s top ten billionaires has grown from £47.77 billion in 2009 to £182 billion in 2022 – an increase of 281%.

Whether or not public sentiment acknowledges it, in that case, it is a material fact that inequality in the UK is expanding. Britain is increasingly divided between a class of hyper-wealthy individuals and the working poor – but then again, it has been that was for more than a decade. What may be interesting about a new report from Kantar Public is not, in that case, that Britain is ‘unfair’, but that voters finally seem to be acknowledging as much.

Having repeatedly returned governments to power which seem relatively unconcerned with the situation, respondents to a poll from the professional services firm seem to have suddenly taken stock of what is going on. 44% of people told the firm in February 2022 that they believed in Britain, the division between ‘haves’ and ‘have-nots’ was “a lot” – but by September that was at 49%. Meanwhile, only 14% were willing to suggest that the gap was non-existent, or too small to care about.

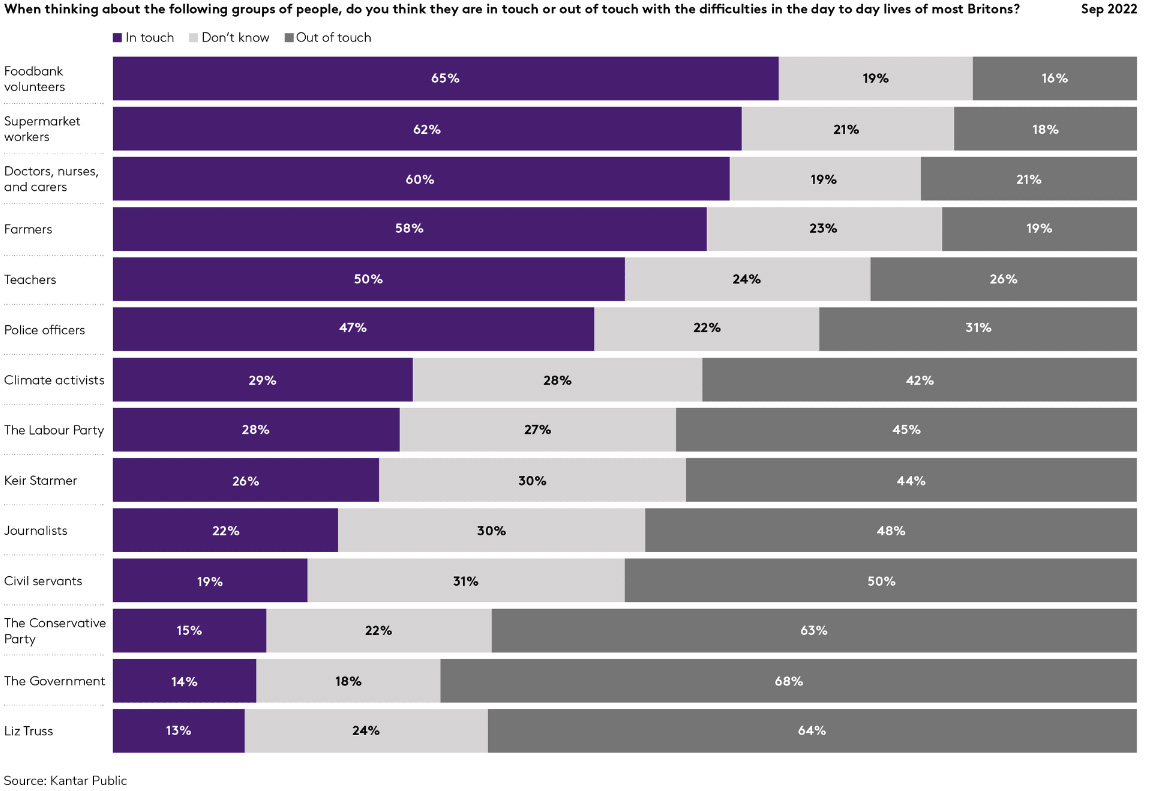

At the same time, a large majority now believe that the incumbent government is too detached from reality to help them. When asked who they felt was ‘in touch’ with the daily struggles of most people in Britain, the largest number of 65% said foodbank volunteers were in touch. In stark contrast, outgoing Prime Minister Liz Truss was seen as out of touch by a similar 64%.

This perceived aloofness seems to have contributed to Truss’ historic ousting – having been forced from office after just 45 days. No other Prime Minister has endured such a brief tenure, but with the leader of the opposition Keith Starmer seem as moderately more in touch – by a slightly underwhelming 26%, it should be noted – the Conservatives felt the time was right to roll the dice ahead of a crunch election in the next two years.

The Tories may struggle to find a replacement who can really help shift that metric though. Even Boris Johnson, the seemingly Teflon-coated buffoon who bumbled his way through scandal after scandal during the pandemic, now seems to be tarred with the same brush as all Conservatives – who 63% of the public see as ‘out of touch’.

When it comes down to how the public want the government to improve public life, Kantar Public’s study suggests that the yawning class divide is ‘lower’ on the agenda than many more immediate factors. Reducing income inequality between rich and poor was fourth on the list, a priority of just over one-fifth of respondents. Meanwhile, reducing the cost of living for households took top priority for more than 50% of respondents – with nearest equivalent ‘investing in the NHS’ listed as a top-three goal by just under 40%.

But with inflation already at a record high, paying for these initiatives by simply ‘printing money’ or borrowing is unfeasible. Imposing taxes on the country’s wealthiest – and so redistributing those funds from the richest to the poorest, and reducing income inequality – may form a key element of delivering either policy.