As global demand for lithium-ion batteries grows rapidly, manufacturers cannot ignore supply chain risks any longer. A new study suggests battery recycling could be a game-changer for businesses looking to secure their supply.

With interest in battery-powered electric vehicles (BEVs) growing rapidly, so too is the need to supply raw materials used in the booming technology. While e-cars accounted for just 4% of global car sales last year, by 2030, this is projected to rise to over 30%. It may further accelerate after this, as the number of countries banning the sale of new combustion-engine-powered transport grows.

Such a surge in demand brings new risks to the lithium-ion battery supply chain, though. While the technology might see automotive dependence on fossil fuels fall, it will increase the need for other raw materials. According to Roland Berger, this may place acute pressure on the supply chain – particularly as a number of issues come to a head within the lithium production sphere.

Commenting on the challenges producers face, Wolfgang Bernhart, Partner at Roland Berger, explained, “Increased raw material costs have already made e-car batteries massively more expensive in recent months. The war in Ukraine is exacerbating this dynamic even further. This will not stop the trend towards e-vehicles, but it can slow it down.”

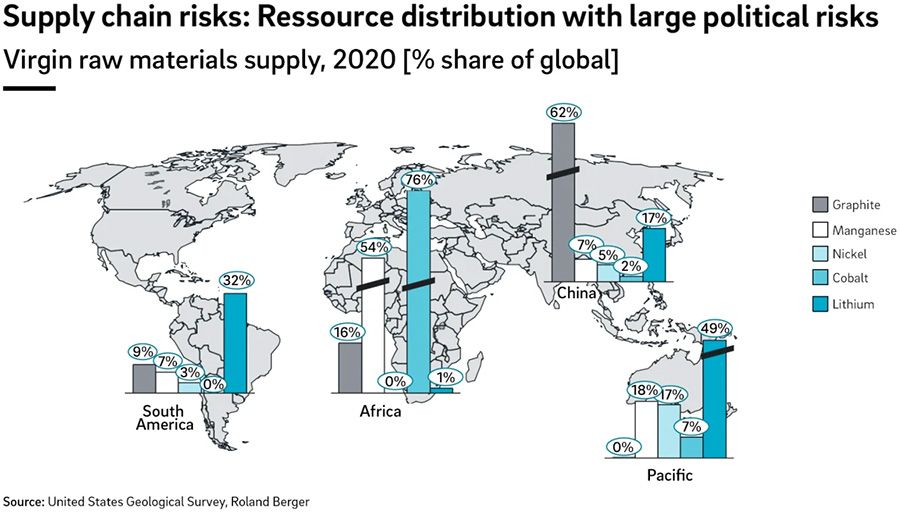

European conflicts are not the only way in which the mining and distribution of resources crucial to battery production are being impacted. Alongside ESG risks (some production processes emit a lot of CO2), geo-political risks are becoming a constant headache for manufacturers. While Australia is a leading market in the production of lithium – with the Pacific region accounting for 49% of global supply in 2020 – China is the third largest lithium market, at 17%. As tensions escalate between the emerging superpower and the US, access to this supply is placed in increasing jeopardy.

At the same time, supply from South America – the second biggest lithium producer at 32% – has been impacted by political instability. Bolivia boasts large reserves of lithium – which the country’s government nationalised to help fund wider its wider economic and social progress. There was an agreement with a German company to go into the production of batteries, but a functioning deal never materialised as a coup overthrew the country’s government.

Such pressures are causing difficulties in obtaining many of the resources needed to produce batteries. And as is usually the case when demand rises and supply falls, this has sent prices sky-high. Ramping up battery production to meet increased demand subsequently will not come cheap. Roland Berger expects a necessary CAPEX of €250-300 billion over the next eight years to be needed for it – with a third of that coming from Europe.

Avoiding these bottlenecks requires changes throughout the supply chain. As lithium-ion battery-operated goods proliferate more widely, so too will the amount of materials which can be recycled when those products reach the end of their life-cycle. According to Roland Berger, while the industry currently produces more scrap metal than recyclable material, this could flip as early as 2027 – driven by the high-recyclability of BEVs in particular.

“At the production level, an integrated approach between metallurgy and chemistry can help reduce costs,” Bernhart added. “More regionalisation and co-location for multiple steps in battery manufacturing can also reduce geopolitical and ESG risks. Recycling will play an increasingly important role from the end of the decade.”