As a number of key UK infrastructure projects such as HS2 face delivery issues, a new study has asked sector leaders how things could be improved. According to the respondents, while firms can do more to boost collaboration and diversity, ultimately the UK Government needs to remove key barriers to progress in the coming months.

UK infrastructure project leaders have endured one of the toughest periods in their modern history. While they showed surprising flexibility during the lockdown phase of a global pandemic, three years on, they face complex issues on all fronts. While war in Ukraine continues to disrupt supply chains and send energy costs soaring, at home a period of heightened political instability has left developers guessing about the kind of regulatory changes they will be facing. According to new research from consulting firm Ankura, it is subsequently taking longer for major infrastructure projects to move from the drawing board to breaking ground.

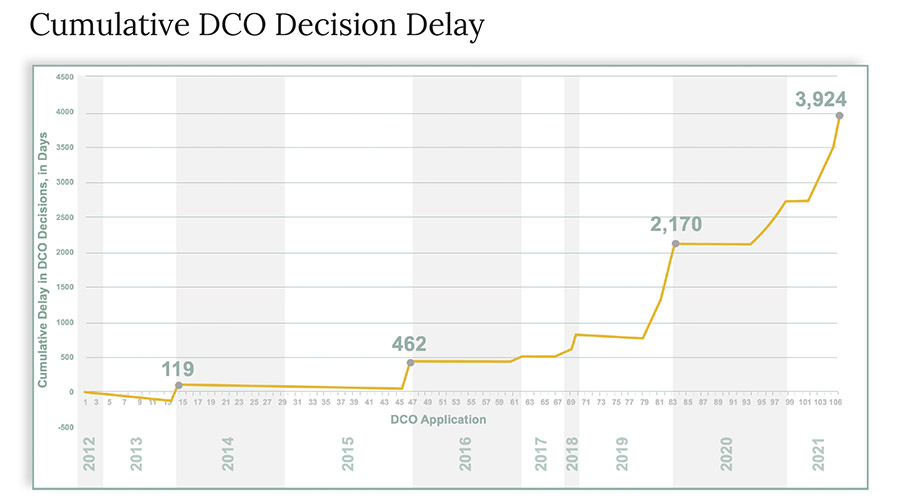

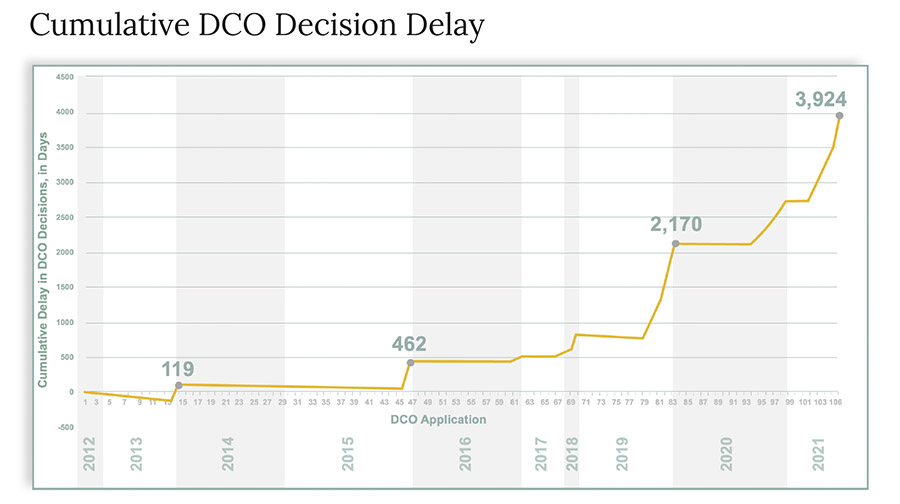

Development Consent Orders (DCOs) are granted by the Secretary of State for Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects (NSIPs) – combining a grant of planning permission with a range of other separate consents, such as listed building consent. Between 2012 and 2016, DCO decisions were largely on time or early, leaving the total delay – calculated as the sum of each DCO decision delay within the period, both positive and negative – at the end of 2016 was 509 days. Over the following five years, though, this soared to almost 4,000 days – with even the HM Treasury acknowledging that “the system has slowed in recent years, with the timespan for granting DCOs increasing by 65% between 2012 and 2021.”

Project leaders and regulators are both looking for ways to get landmark construction projects back on track in the UK. The Treasury, for instance, has tasked the National Infrastructure Commission with providing recommendations. Ankura has also consulted construction sector leaders to find out how they think things might be improved – and come up with five key tips in the process.

Collaboration

While Ankura asserts that UK infrastructure is “known for world-leading innovation that solves the most complex of problems”, the researchers find it is often “confined within the boundaries of individual projects”. Addressing the industry’s biggest challenges – from net zero to digitalisation and talent gaps – will require the breaking down of ‘innovation silos’ to ensure knowledge and capabilities that could apply across multiple areas, are not just confined to one place.

At present, Ankura finds that knowledge sharing does take place, but the leaders who spoke to the firm also acknowledged that more innovation across projects and sectors could do more to harness the collective investment power of UK infrastructure. As all clients are grappling with the same fundamental set of challenges, pooling resources – both talent and capital – becomes logical, even if the mechanics of how this might work in practice are not immediately obvious, following decades of dog-eat-dog competition, and the previous fragmentation of supply chains. Even so, learning to move beyond this, and enable project delivery without starting from scratch every time, ultimately benefits everyone.

Decision process

This could play a key role in helping address the increasingly difficult period of preparing for a planning examination. Partly driven by ever-extending timescales, planning examinations are becoming more expensive. The longer the process takes, the more rework is needed to keep up to date, while the more change that occurs, the larger the support teams, and the longer they need to be involved. At a time when hiring new talent has become more difficult, amid historically high levels of employment, collaboration can open up knowhow at relevant times in a quicker and more cost-effective manner.

Even so, against the current economic backdrop, a faster and lower cost planning regime is needed, which can provide earlier certainty. Industry leaders told Ankura that the current regulatory and political environment is “not only pausing the next generation of major projects”, it is also “seriously damaging the UK’s ability to deliver world-leading projects by driving down confidence [and] reasons to invest”. If regulators do not react, this could lead to a skills gap across the sector, with investors, employers and skilled workers ultimately considering well-funded giga-projects, such as NEOM – however absurd they might find them – a “greater allure” than “a UK redevelopment that may or may not happen”.

Diversity

The UK’s construction sector is already grappling with a skills shortage as it is. With high levels of employment, and heightened employee turnover still lingering from the ‘Great Resignation’ of 2021, employers are finding it hard to fill vacancies with talent that they have traditionally favoured. Fostering a culture of inviting “all minds at the table” could be key to overcoming this, according to Ankura.

While there has been some slow progress when it comes to balancing the gender-makeup of construction, it is still way behind other industries. ONS data shows that 15% of the UK’s construction workforce is female, while analysis by GBM, the union for the UK’s construction sector, suggests that on this rate of progress it will take almost 200 years to achieve gender equality. Doing something to fast-track those changes and better utilise a marginalised source of labour could help plug the skills shortage in the sector, though. To that end, making the sector more appealing in terms of progression seems imperative. At present, women disproportionately account for just 2.1% of manager and director roles in construction.

Public sector risk affinity

The time leading up to planning consent is the optimal window in which to innovate, but projects lack the funding to do so at this stage. One of the 2021 participants of Ankura’s study suggested that while “there are no rewards for getting it right,” there is “plenty of criticism for getting it wrong”. Two years later, the risk aversion of the public sector seems only to have grown, with respondents informing Ankura that there is a lack of public funding for innovations which could help the construction sector work answer key problems, including climate change. Meanwhile, even when the UK Government publishes a pipeline of infrastructure projects, the pipeline is not binding – meaning attracting private sector investors is difficult.

To change this, leaders told Ankura that the UK Government must embrace calculated risk to drive progress. This requires institutional change at the state level – providing a new framework with more certainty to at least inspire more confidence from private sector investors.

Digital gap

Finally, while the need to digitalise the sector has been widely talked about for some time, progress remains slow. To that end, Ankura finds that a shift in attitudes to transparency “could unlock significant improvements in performance”, allowing for the UK construction sector to capitalise on the latest advances in technology.

This is because, relating back to the history of competition between firms, participants told Ankura that the sector largely has an anti-transparency mindset relating to its information. They highlighted unwillingness for data sharing across the supply chain – with the sharing of information reflexively ruled out due to worries intellectual property rights may be lost, among other issues. But gains from data transparency across infrastructure projects could be enormous, lifting the lid on the pros and cons of current operational performance, and allowing improvement and optimisation to occur responsively as projects are delivered.