UK universities are facing a financial crunch, the effects of which are already being felt across the higher education sector. This is putting increasing pressure on universities to recruit international students – who pay higher tuition fee rates – to make ends meet; and many are turning to private sector partnerships to help them compete with other universities for this lucrative pipeline.

The marketisation of higher education in the UK is a process which has been unfolding gradually for 25 years, now. Tuition fees were first introduced in the UK in 1998, as a means of eventually seeing 50% of the population go to university – as it would enable a higher level of funding to be sunk into the higher education system, without the need for public spending. While the first tuition feeds stood at around £1,000 per year, that figure has since been controversially upped to a £9,000 figure – while public spending on higher education has been scaled back.

With UK universities increasingly dependent on fees for their income, many realised that courting international students would be a way to further maximise revenues – as they could charge more for students from overseas, while offering the same service to them as domestic students. In the years after the 2016 Brexit vote, however, the precarity of this position became increasingly apparent to university leaders. With the flow of new students from overseas potentially being stymied by new visas and other immigration controls, especially with Brexit likely to drastically reduce the number of EU students arriving to study in the UK, 97% said this could be damaging – and 46%, highly damaging.

Now, it is clear that those damages are manifesting. The 2021-22 academic year saw an unprecedented 53% fall in the number of first-year EU students enrolling at British universities. And EU students were not the only ones going elsewhere. China – which has for the longest time provided a pipeline of lucrative international students from the nation’s burgeoning middle class – also seems to be turning away, due both to the pandemic, and the rising status of the nation’s own universities. Applications from China to UK universities had quadrupled between 2014 and 2021 – but last year they decreased for the first time, falling by 4.2%.

With the funding structure of universities now dependent on attracting new ‘customers’ at an ever higher rate, this presents an existential threat to many institutions – and has already led to stringent spending cuts and layoffs in some of the UK’s most prominent establishments. At the same time, though, more universities are looking to pivot their offering to new international markets, as a means to secure fees in the future. To do this, a growing number are turning to private sector partnerships for support – according to new research from Nous Group.

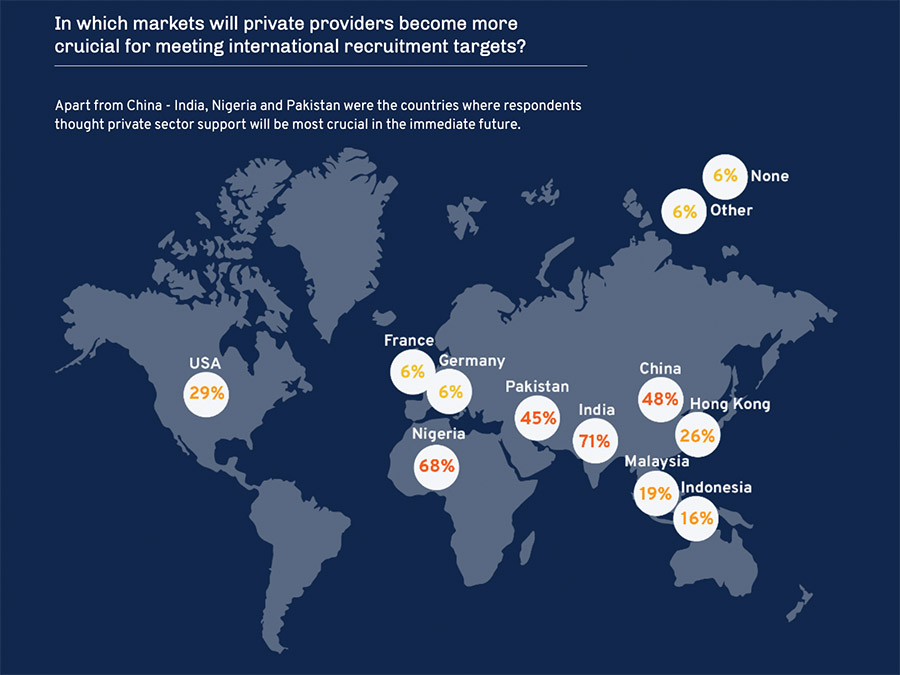

With EU students and China’s next generation of academics both moving away from UK universities, university leaders do not see the role of private providers being as important there as in several other growing economies. In particular, 68% said Nigeria and 71% said India would be the most important markets to help recruit within. This already seems to be paying dividends – with applications from Nigeria having reportedly risen by 23% in the last year, helping overall international applications rise by a narrow 3%.

Nous Principal Matt Durnin, who authored the report, commented, “International recruitment teams are increasingly pressed to deliver bigger results without corresponding investments in resources, which forces innovative thinking about the role the private sector can play. This trend was in motion before 2020, but the pandemic and a surge of venture capital into educational services in recent years have accelerated the development of private provider services.”

When Nous asked university leaders why they were contracting private firms to aid recruitment drives, many were clear that the importance of international fees meant they could not afford to be left behind by other institutions. A 72% majority believed private firms could help them amid increased competition for international recruitment to that end. At the same time, 47% said that they needed to provide additional services to help with this level of competition, which they currently did not have capacity for – while acknowledging they needed to prioritise “what we are good at” in the delivery of higher education.

Overall, 47% of the UK universities the report surveyed had increased the use of private providers in their international student recruitment efforts since the Covid-19 pandemic. Not all universities agreed there was inherent value in engaging private providers, however. The report also found that many larger, higher-ranking universities believed trading on their brand would be enough, making them hesitant to engage private providers until the private sector had proved its value. At the same time, some lower-ranked universities were reluctant to engage private providers because they lack sufficient resources to evaluate and navigate relations with the sector.